GT Investigates: Records from US, UK provide solid proof of China’s sovereignty over South China Sea islands

Editor's Note:

The activities of the Chinese people in the South China Sea date back over 2,000 years. China is the first to have discovered, named, explored, and utilized the maritime resources on and around Nansha Qundao and relevant waters, and the first to have continuously, peacefully, and effectively exercised sovereignty and jurisdiction over them. Silent archaeological relics are faithful witnesses to this.

The Global Times is launching the series "Artifacts Tell South China Sea Truth." Through historical relics, maps, and other materials from ancient and modern times, both at home and abroad, the evidences will show how China's territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea have long been clearly recorded and recognized by world history.

This is the second installment in the series, focusing on what historical maps, authoritative historical materials, and empirical archives support the legitimacy of China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

Incestigates

British official archives provide evidence regard China's sovereignty over South China Sea islands

China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is indisputable, rooted not only in a long history of practice, but also widely recognized by the international community. A representative and authoritative memorandum from British official archives provides clear evidence supporting this claim.

Looking back to the mid-20th century, the UK once harbored ambitions regarding the reefs and islands in the South China Sea, attempting to incorporate them into its sphere of influence. However, constrained by the evolving international landscape and a lack of historical and legal justification for its claims, the UK ultimately chose to set aside and abandon this aspiration. Since the 1930s, the UK has consistently monitored the disputes over sovereignty of the South China Sea islands involving China, France, Japan, and other neighboring countries, maintaining a role as an "observer" and "intelligence gatherer" to track regional developments.

As time progressed into the 1970s, tensions in the South China Sea escalated sharply due to the large-scale occupation of Nansha Qundao by certain neighboring countries. In response to this shift, the UK did not remain aloof; rather, it intensified its research on the South China Sea issue. Through long-term internal assessments, the UK demonstrated a degree of objectivity.

In February 1974, after reviewing and comparing the basic historical facts and viewpoints of all claimants (including the UK), E. M. Denza, then one of the legal advisers of the British Foreign Ministry, produced an influential memorandum on "The Spratly Islands [the Nansha Islands]."

This memorandum was subsequently stored in the UK National Archives, becoming an important reference for the UK government in addressing South China Sea issues, with its influence continuing to this day.

According to the copy of memorandum provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources to the Global Times, from an international law perspective, the memorandum first clarifies the UK's own position: "The British view at the beginning of the 20th century appears to have been that the islands were a Chinese responsibility. By the 1920s, when the French became interested in the islands, Britain was inclined to favor the Chinese claim against the French, for strategic reasons."

To support this judgment, the memorandum emphasizes the historical continuity of China's sovereignty claims: China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands can be traced back to the 15th century, with a complete trajectory of sovereignty exercise developed over hundreds of years.GT:

Chen Xidi, an expert at the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, told the Global Times that the views expressed in this memorandum provided critical reference for the British government at the time and have been frequently cited by British diplomats and researchers, holding considerable authority and essentially representing the official position of the British Foreign Office on the issue of sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

"Thus, it is evident that China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is an objective fact supported by ample historical and legal evidence, and has been widely recognized by many members of the international community, including the UK," he said.

In a previous interview with the Global Times, Anthony Carty, an Irish international law professor who currently serves as a visiting professor at the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences of Peking University and a professor at the School of Law of Beijing Institute of Technology, and who has authored a book, The History and Sovereignty of South China Sea, demonstrating China's indisputable sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands, offered key insights into archival evidence.

Carty noted that they are complex archives going from the 1880s until the late 1970s. The key archives are probably the French, the British are observing the French and the Chinese. "The archives demonstrate, taken as a whole, that it is the view of the British and French legal experts that as a matter of the international law territory, which is a rather arcane subject, the Xisha Islands and the Nansha Islands are Chinese territory," he emphasized.

This expert perspective, paired with the conclusions of Britain's official archives like the memorandum, further reinforces that China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is not merely a historical fact, but a position validated by international legal analysis and cross-national archival evidence.

US maps from early 20th century confirm China's indisputable sovereignty over Huangyan Dao

By sorting through and researching several historical maps from 1898 to 1908 and a series of authoritative historical materials, the Global Times has found that the context of Huangyan Dao's ownership is clearly discernible: From the US acquisition of control over the Philippines after the Spanish-American War in the late 19th century to the preservation of relevant historical documents in the mid-20th century, the US never incorporated Huangyan Dao into its territorial scope during its rule over the Philippines. These empirical archives not only refute the current unwarranted territorial claims to Huangyan Dao by the Philippines at the source, but also confirm the solid foundation of Huangyan Dao as China's inherent territory from both historical and legal perspectives.

The outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 marked a key turning point in reshaping the Philippines' territorial ownership. In March of that year, the US and Spain went to war, and the conflict quickly spread to Spain's colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. That August, US troops occupied Manila, the capital of the Philippines, bringing the war to an end with a US victory. The subsequent Treaty of Peace between the United States and Spain (commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898) became the core legal basis for the US to define the territorial scope of the Philippines. The treaty explicitly stipulated that Spain would cede the Philippines to the US, but Huangyan Dao was clearly excluded from the scope of the cession. This agreement not only established the benchmark for territorial boundaries during the US rule over the Philippines, but also demonstrated from a legal origin that the US did not regard Huangyan Dao as part of the Philippines' territory from the very beginning of its acquisition of control over the Philippines.

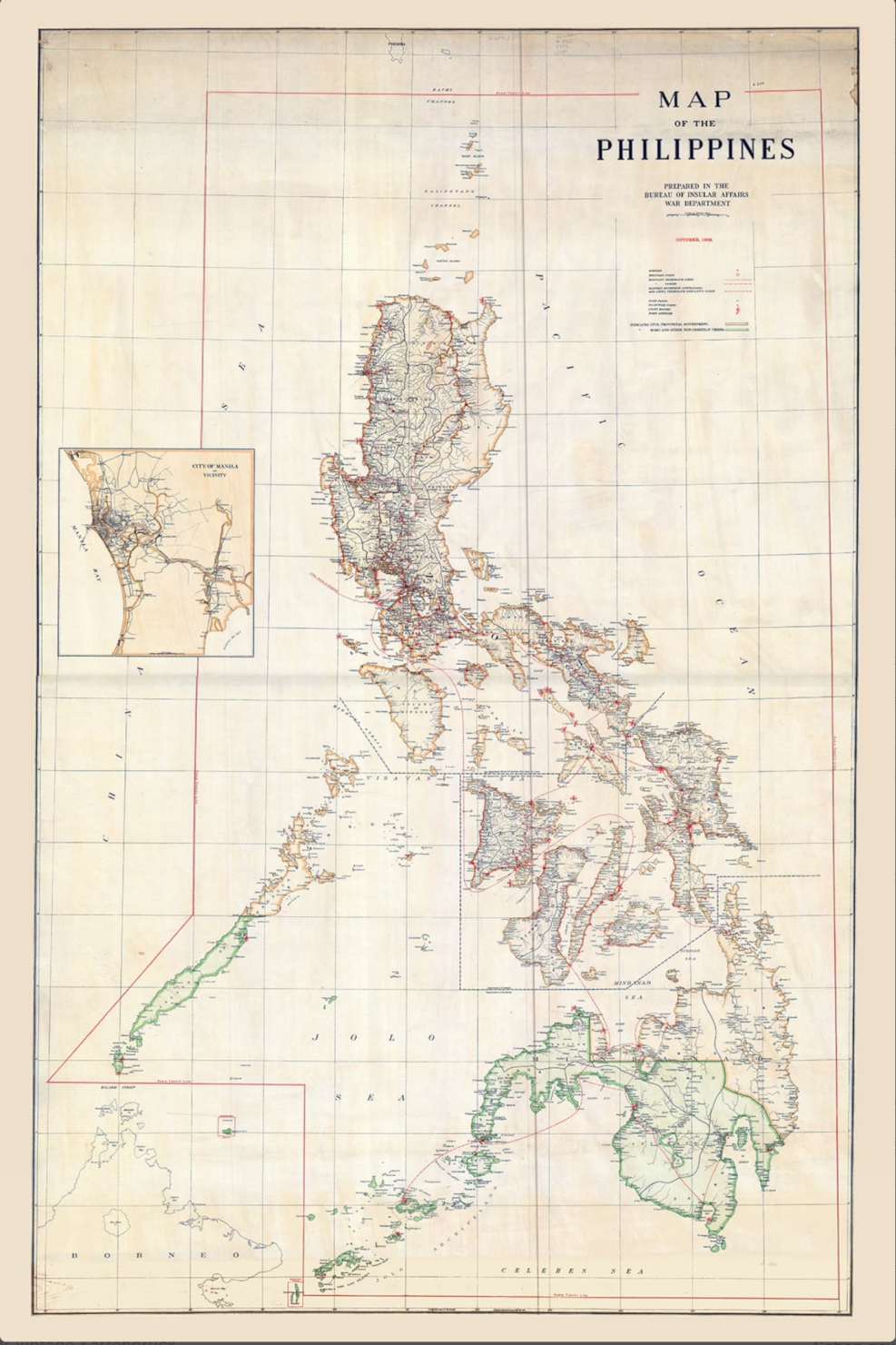

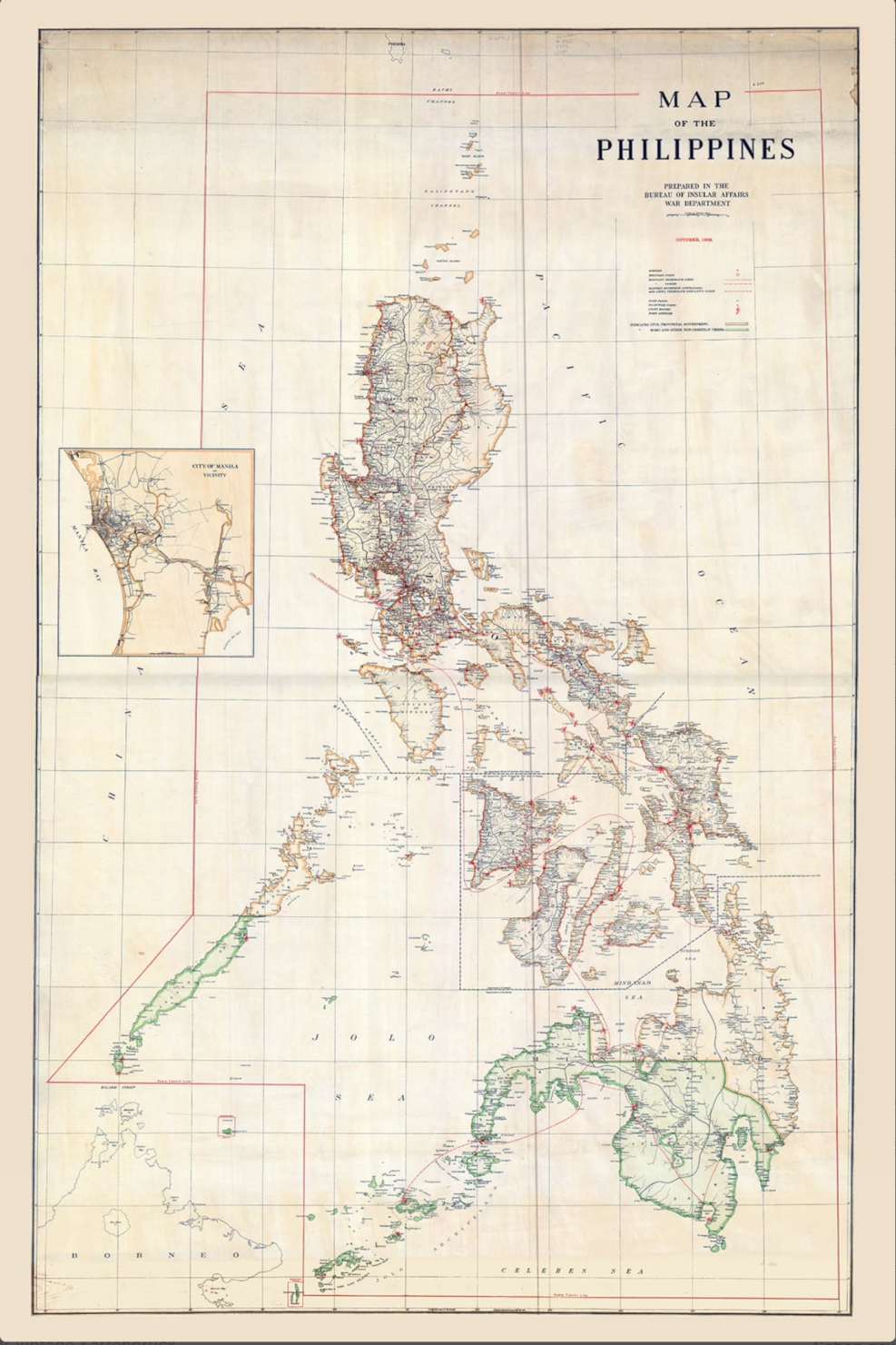

This territorial delineation was not only codified in legal text, but also consistently visualized in official maps published by the US and Philippine authorities. In 1898, the US government approved the publication of an English-language map of the Philippine Islands, which, as discovered by the Global Times in the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, marked the western boundary of the Philippines at 118° East longitude. Huangyan Dao, however, is situated at 117°51 East longitude, placing it unmistakably outside this boundary.

In 1902, the Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Department (later transferred to the US Department of the Treasury) published another map of the Philippines. As an official administrative product, this map adhered to the 1898 boundary demarcation, once again excluding Huangyan Dao from Philippine territory, according to the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources.

By 1908, the New York-based World Book Company published the "Map of the Philippine Islands," which credited key US federal agencies, including the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, the Military Information Division of the War Department, and the Hydrographic Office of the Navy Department, with providing essential data. In the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Global Times also found several Philippine government agencies, such as the Bureau of Education, Bureau of Public Works, and Bureau of Science (including its Ethnological Survey), also participated in the map's compilation. Despite this collaborative effort, the map still depicted Huangyan Dao outside the Philippines' national boundaries.

Further historical details emerged in the 1930s. The Nationalist government's Water and Land Map Review Commission reviewed and approved the Chinese and English names of the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, which included Huangyan Dao as part of China's territory. The US government raised no objection to this assertion, implicitly acknowledging the island's link to China.

In December 1937, amid concerns about Japanese expansion, the US-administered Philippine government proposed constructing military installations on Huangyan Dao. This prompted internal discussions among US departments. The paper "Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal" by François-Xavier Bonnet, published in Irasec's Discussion Papers, an online publication on contemporary issues in Southeast Asia, in 2012, shows that by March 1938, the US Secretary of State explicitly stated in a cable to the Secretary of War that Huangyan Dao lay outside the territorial limits of the Philippines as defined by the Treaty of Paris of 1898. Not long after, due to Japan's southward invasion, the US lost its Philippine colony and had no further connection with Huangyan Dao.

From the legal definition in the 1898 treaty between the US and Spain, to the consistent depictions in official maps from 1898 to 1908, and the explicit US government stance in 1938, a coherent and conclusive evidence chain emerges.

Chen Xidi, an expert at the China Institute for Marine Affairs of the Ministry of Natural Resources, told the Global Times that the US government's position was clear and consistent: Huangyan Dao was always excluded from the Philippines' boundaries.

"This stance, rooted in international law and historical fact, legally binds the modern Philippine government. Beyond a doubt, Huangyan Dao is an inherent and indivisible part of China, a fact widely recognized and supported by the international community," Chen said.

The activities of the Chinese people in the South China Sea date back over 2,000 years. China is the first to have discovered, named, explored, and utilized the maritime resources on and around Nansha Qundao and relevant waters, and the first to have continuously, peacefully, and effectively exercised sovereignty and jurisdiction over them. Silent archaeological relics are faithful witnesses to this.

The Global Times is launching the series "Artifacts Tell South China Sea Truth." Through historical relics, maps, and other materials from ancient and modern times, both at home and abroad, the evidences will show how China's territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea have long been clearly recorded and recognized by world history.

This is the second installment in the series, focusing on what historical maps, authoritative historical materials, and empirical archives support the legitimacy of China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

Incestigates

British official archives provide evidence regard China's sovereignty over South China Sea islands

China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is indisputable, rooted not only in a long history of practice, but also widely recognized by the international community. A representative and authoritative memorandum from British official archives provides clear evidence supporting this claim.

Looking back to the mid-20th century, the UK once harbored ambitions regarding the reefs and islands in the South China Sea, attempting to incorporate them into its sphere of influence. However, constrained by the evolving international landscape and a lack of historical and legal justification for its claims, the UK ultimately chose to set aside and abandon this aspiration. Since the 1930s, the UK has consistently monitored the disputes over sovereignty of the South China Sea islands involving China, France, Japan, and other neighboring countries, maintaining a role as an "observer" and "intelligence gatherer" to track regional developments.

As time progressed into the 1970s, tensions in the South China Sea escalated sharply due to the large-scale occupation of Nansha Qundao by certain neighboring countries. In response to this shift, the UK did not remain aloof; rather, it intensified its research on the South China Sea issue. Through long-term internal assessments, the UK demonstrated a degree of objectivity.

In February 1974, after reviewing and comparing the basic historical facts and viewpoints of all claimants (including the UK), E. M. Denza, then one of the legal advisers of the British Foreign Ministry, produced an influential memorandum on "The Spratly Islands [the Nansha Islands]."

This memorandum was subsequently stored in the UK National Archives, becoming an important reference for the UK government in addressing South China Sea issues, with its influence continuing to this day.

According to the copy of memorandum provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources to the Global Times, from an international law perspective, the memorandum first clarifies the UK's own position: "The British view at the beginning of the 20th century appears to have been that the islands were a Chinese responsibility. By the 1920s, when the French became interested in the islands, Britain was inclined to favor the Chinese claim against the French, for strategic reasons."

To support this judgment, the memorandum emphasizes the historical continuity of China's sovereignty claims: China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands can be traced back to the 15th century, with a complete trajectory of sovereignty exercise developed over hundreds of years.GT:

Chen Xidi, an expert at the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, told the Global Times that the views expressed in this memorandum provided critical reference for the British government at the time and have been frequently cited by British diplomats and researchers, holding considerable authority and essentially representing the official position of the British Foreign Office on the issue of sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

"Thus, it is evident that China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is an objective fact supported by ample historical and legal evidence, and has been widely recognized by many members of the international community, including the UK," he said.

In a previous interview with the Global Times, Anthony Carty, an Irish international law professor who currently serves as a visiting professor at the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences of Peking University and a professor at the School of Law of Beijing Institute of Technology, and who has authored a book, The History and Sovereignty of South China Sea, demonstrating China's indisputable sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands, offered key insights into archival evidence.

Carty noted that they are complex archives going from the 1880s until the late 1970s. The key archives are probably the French, the British are observing the French and the Chinese. "The archives demonstrate, taken as a whole, that it is the view of the British and French legal experts that as a matter of the international law territory, which is a rather arcane subject, the Xisha Islands and the Nansha Islands are Chinese territory," he emphasized.

This expert perspective, paired with the conclusions of Britain's official archives like the memorandum, further reinforces that China's sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is not merely a historical fact, but a position validated by international legal analysis and cross-national archival evidence.

The map of the Philippines published by Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Department of the US in 1902 Photo: Courtesy of China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources

US maps from early 20th century confirm China's indisputable sovereignty over Huangyan Dao

By sorting through and researching several historical maps from 1898 to 1908 and a series of authoritative historical materials, the Global Times has found that the context of Huangyan Dao's ownership is clearly discernible: From the US acquisition of control over the Philippines after the Spanish-American War in the late 19th century to the preservation of relevant historical documents in the mid-20th century, the US never incorporated Huangyan Dao into its territorial scope during its rule over the Philippines. These empirical archives not only refute the current unwarranted territorial claims to Huangyan Dao by the Philippines at the source, but also confirm the solid foundation of Huangyan Dao as China's inherent territory from both historical and legal perspectives.

The outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 marked a key turning point in reshaping the Philippines' territorial ownership. In March of that year, the US and Spain went to war, and the conflict quickly spread to Spain's colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. That August, US troops occupied Manila, the capital of the Philippines, bringing the war to an end with a US victory. The subsequent Treaty of Peace between the United States and Spain (commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898) became the core legal basis for the US to define the territorial scope of the Philippines. The treaty explicitly stipulated that Spain would cede the Philippines to the US, but Huangyan Dao was clearly excluded from the scope of the cession. This agreement not only established the benchmark for territorial boundaries during the US rule over the Philippines, but also demonstrated from a legal origin that the US did not regard Huangyan Dao as part of the Philippines' territory from the very beginning of its acquisition of control over the Philippines.

This territorial delineation was not only codified in legal text, but also consistently visualized in official maps published by the US and Philippine authorities. In 1898, the US government approved the publication of an English-language map of the Philippine Islands, which, as discovered by the Global Times in the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, marked the western boundary of the Philippines at 118° East longitude. Huangyan Dao, however, is situated at 117°51 East longitude, placing it unmistakably outside this boundary.

In 1902, the Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Department (later transferred to the US Department of the Treasury) published another map of the Philippines. As an official administrative product, this map adhered to the 1898 boundary demarcation, once again excluding Huangyan Dao from Philippine territory, according to the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources.

By 1908, the New York-based World Book Company published the "Map of the Philippine Islands," which credited key US federal agencies, including the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, the Military Information Division of the War Department, and the Hydrographic Office of the Navy Department, with providing essential data. In the copy provided by the China Institute for Marine Affairs at the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Global Times also found several Philippine government agencies, such as the Bureau of Education, Bureau of Public Works, and Bureau of Science (including its Ethnological Survey), also participated in the map's compilation. Despite this collaborative effort, the map still depicted Huangyan Dao outside the Philippines' national boundaries.

Further historical details emerged in the 1930s. The Nationalist government's Water and Land Map Review Commission reviewed and approved the Chinese and English names of the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, which included Huangyan Dao as part of China's territory. The US government raised no objection to this assertion, implicitly acknowledging the island's link to China.

In December 1937, amid concerns about Japanese expansion, the US-administered Philippine government proposed constructing military installations on Huangyan Dao. This prompted internal discussions among US departments. The paper "Geopolitics of Scarborough Shoal" by François-Xavier Bonnet, published in Irasec's Discussion Papers, an online publication on contemporary issues in Southeast Asia, in 2012, shows that by March 1938, the US Secretary of State explicitly stated in a cable to the Secretary of War that Huangyan Dao lay outside the territorial limits of the Philippines as defined by the Treaty of Paris of 1898. Not long after, due to Japan's southward invasion, the US lost its Philippine colony and had no further connection with Huangyan Dao.

From the legal definition in the 1898 treaty between the US and Spain, to the consistent depictions in official maps from 1898 to 1908, and the explicit US government stance in 1938, a coherent and conclusive evidence chain emerges.

Chen Xidi, an expert at the China Institute for Marine Affairs of the Ministry of Natural Resources, told the Global Times that the US government's position was clear and consistent: Huangyan Dao was always excluded from the Philippines' boundaries.

"This stance, rooted in international law and historical fact, legally binds the modern Philippine government. Beyond a doubt, Huangyan Dao is an inherent and indivisible part of China, a fact widely recognized and supported by the international community," Chen said.

No comments:

Post a Comment